Quantum Dot Spin Qubit Experiments Jun. 2020 – Jun. 2025

⌜Developed comprehensive simulation frameworks to model complex quantum phenomena in semiconductor qubits. Created a full, end-to-end simulation package that computes electron wavefunctions from CAD layouts by solving the Schrödinger equation, and convolves them with MuMax3-simulated magnetic fields. Utilized QuTiP to solve the quantum master equation with Lindblad operators to reproduce experimental observations of qubit-environment interactions in silicon. Modeled dynamic nuclear polarization in GaAs dots using a modified Hubbard model.⌟

To complement my experimental work, I have developed a strong expertise in computational modeling to understand the complex physics governing quantum dot systems.

My initial work focused on explaining the bidirectional dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP) observed in GaAs singlet-triplet qubits.

By modeling the system with a modified Hubbard model that incorporated excited-level spin mixing, my simulation successfully reproduced the experimental DNP behavior, providing a theoretical explanation for this previously unexplained phenomenon.

The details can be found in my Master's thesis.

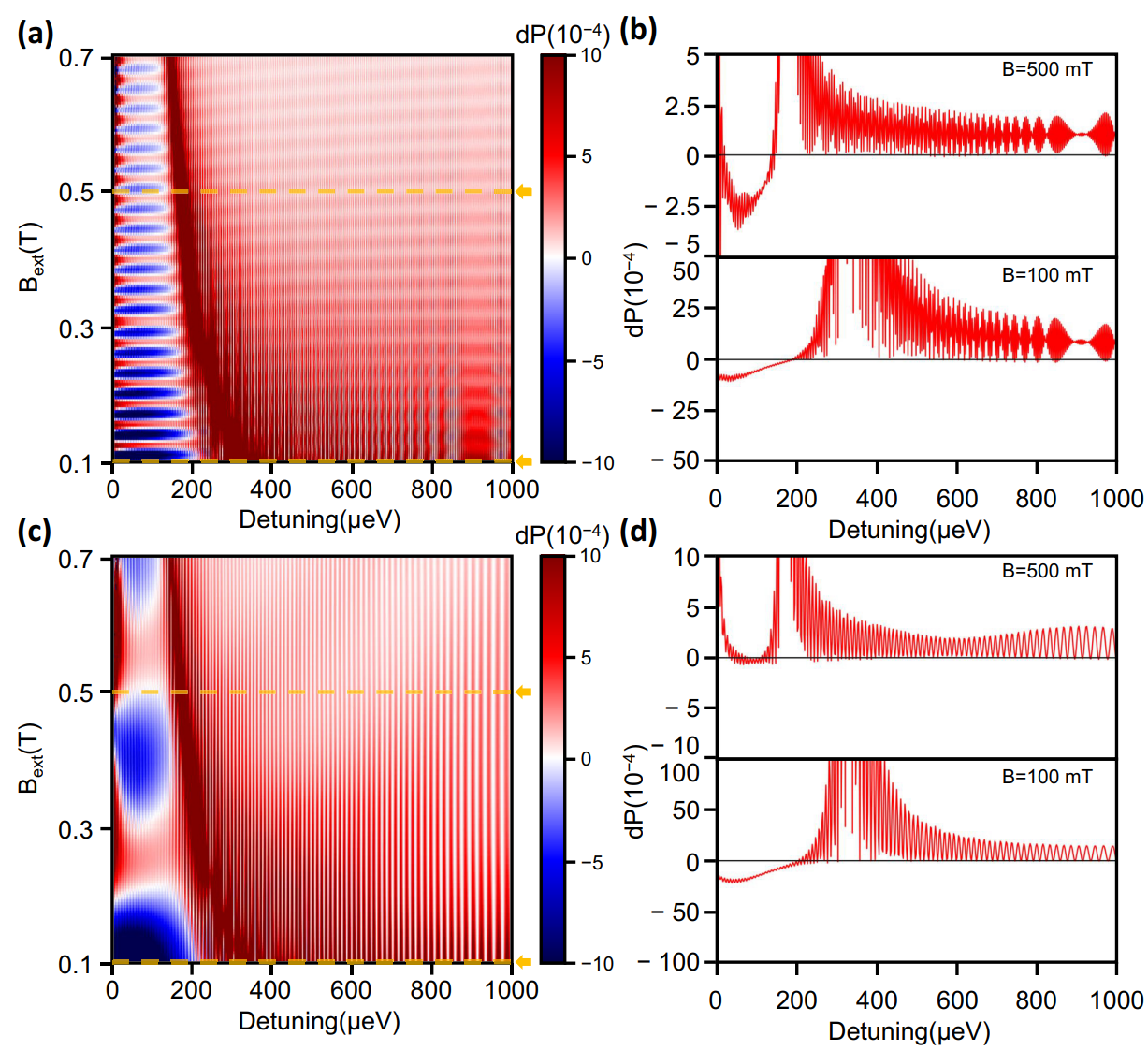

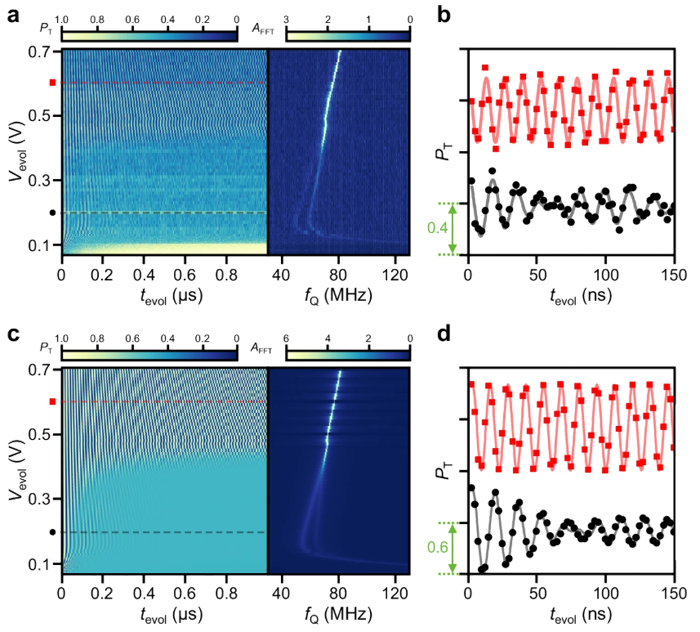

Building on this experience, I later used the QuTiP (Quantum Toolbox in Python) framework to investigate the coherent interaction between a singlet-triplet qubit and a neighboring multi-electron quantum dot in a 28Si/SiGe device.

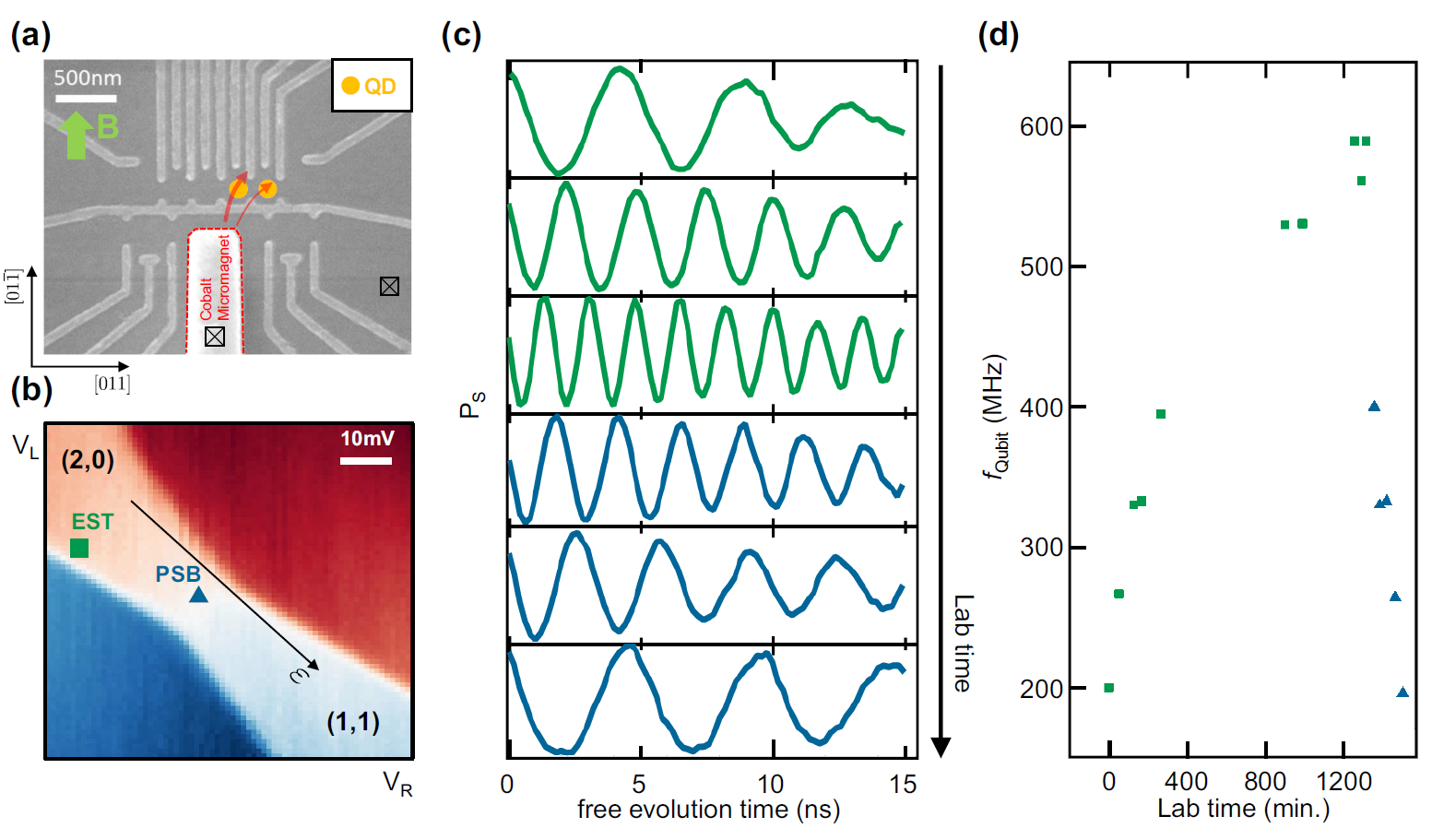

To explain the characteristic beating and dephasing observed in Ramsey measurements (as seen in Figs. 2c and 3c of our npj Quantum Information publication),

I solved the quantum master equation for the coupled system, introducing a phenomenological Lindbladian for dephasing.

These computationally intensive simulations were accelerated by leveraging Python's multiprocessing capabilities to parallelize the calculations.

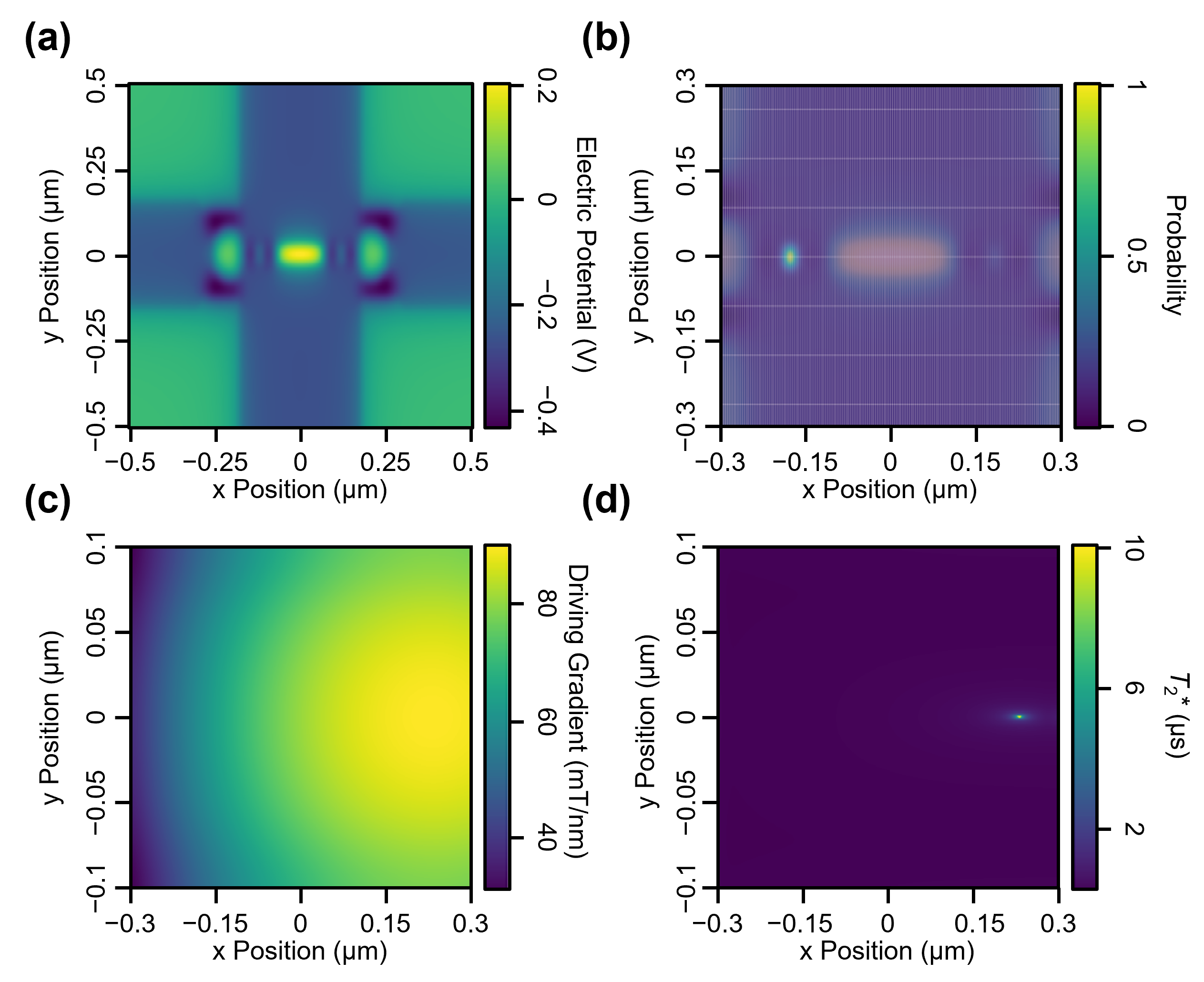

Most recently, to investigate an anomalously long coherence time observed in a silicon device, I developed a full, end-to-end simulation package that connects device geometry to quantum mechanical properties.

This package features a pipeline that: (1) Parses device layouts from CAD files using a custom Python tool, (2) Calculates the 2D electrostatic potential landscape, (3) Solves the 2D Schrödinger equation using a Finite Difference Method to obtain the electron wavefunction, (4) Simulates the micromagnet's 3D stray field using MuMax3, and finally, (5) Convolves the wavefunction with the stray field to compute the effective magnetic field experienced by the qubit.

To accelerate this computationally intensive step, the core calculation was implemented in C++ utilizing multithreading, which achieved a nearly 100x speedup compared to a pure Python implementation. This high-performance C++ backend was then seamlessly integrated into the Python workflow using Pybind11.

This tool, some of which can be found at this link, enables rapid design validation and a deeper understanding of the physics underlying our experimental results.